Rewilding – making a piece of ecological sound art, and reflections on its ability to bring about pro-environmental behaviour.

This blog is an excerpt from an article I wrote for the Wildlife Sound Recording Society’s journal, Volume 14 No.6 - Autumn 2019. My later blog post (05/09/2019) contains some further thinking on ecological sound art and it’s potential to initiate pro-environmental behaviour. Rewilding (2019) can be viewed/listened to via the ‘Sound Art & Design’ section of this website.

In 2017 I was half-way through a degree in Creative Music Technology at Huddersfield University and becoming more and more interested in composing with sound in its widest sense (including field recordings), as opposed to limiting myself to the use of musical notes. Over the course of the summer I attended a Sound and Environment conference at Hull University and discovered that a small but significant body of sound art dealing with environmental issues now exists, such that the academic Jono Gilmurray has argued for the creation of the sub-genre: ‘Ecological Sound Art’ - sound art that is not just inspired by the environment in some way (such as using environmental sounds), but which is also environmentalist and “whose content or subject matter actively engages with ecological issues” (Gilmurray, 2018, p.41). At the conference, as I listened to the various speakers, performances and installations, I had the idea of making my own piece of ecological sound art, based on my local environment. Prior to studying I had spent many years working in the environmental sector for the Environment Agency and whilst I had now left this world behind for creative pursuits, my environmentalism remained deeply important to me. Ecological sound art felt like a way to bring these two areas of interest together, on top of which I was excited by the idea of using sound creatively and as a form of activism, to raise environmental awareness, and possibly even promote pro-environmental behaviour.

I live in West Yorkshire on the edge of the South Pennine moors. The landscape holds a stark, dramatic beauty, but I also consider this environment to represent a relatively barren and ecologically impoverished place, over-managed for certain activities including sheep farming and grouse shooting, to the detriment of native wildlife. In recent years local flooding of homes and businesses has become an increasingly common occurrence, only exacerbated by the lack of trees and other vegetative cover that might otherwise mitigate run-off from the steep slopes. I decided my piece of ecological sound art would be called Rewilding and take the form of an audio-visual journey from present conditions to a richer, more vibrant alternative reality – one where the moorland had been released from existing management regimes and nature had been left to take its course. In my mind’s eye (and ear) I imagined Rewilding would take a linear form, gradually escalating from the stillness (and relative lifelessness) of today’s conditions to an increasingly complex soundscape, representing the growing abundance of returning wildlife.

I spent some time at the early stages of the creative process finding out more about the local moors, and the changes that had taken place through geological and more recent times. It was important for me that any alternative reality presented in the piece was one that had benefited from some investigation into what might be possible – that the sights and sounds, whilst artistically framed, were also not ones beyond the realms of possibility but instead, a future that could exist if we made different choices.

Whilst there is a predominance of tussocky grasses and rushes, rough sheep pasture and managed heather moor where I live there are also pockets of more natural habitat such as heather scrub, grassland meadow and mature woodland. Thus, in the main I didn’t need to venture further than my immediate environs to collect the audio material I needed for the piece. Over the course of the next year and a half, on my forays out, I gained an intimate knowledge of my locality, and began to understand each of the habitats I spent time in (e.g. tussocks, pasture, grouse moor, etc) as having their own distinct sonic and visual identity. I took in their ambiences but also investigated the more hidden sounds, the ones seldom dwelt on, or inaudible to the human ear, such as the creaking inner workings of wind turbines, and the subtly different sonic signatures of various reeds, grasses and sedges swishing and rustling in the wind.

On more than one occasion my intentions for field trips and the sounds I was aiming to capture were de-railed once I got out. A foray into the moors in search of the call of the red grouse resulted instead in me coming upon the delicate electrical glitches of two adjacent pylons. I sat down between them, and with headphones on became absorbed in a long, stereo recording – intricate static dialogue across the summer evening air, backdropped with the rustle of tussocks, and occasional curlew. On my way back to the car I was distracted again, through a fence, over a drainage ditch and deep into the tussocks, by the call of an elusive grasshopper warbler. I did eventually in the course of other field trips manage to capture red grouse calling, but never close-up. My experience was that they make their distinctive call only very occasionally, and maybe not necessarily to attract a mate, or defend a territory but when they are disturbed and flying off. Recording success is possibly best achieved as a two-person mission – one to walk along in the hope of stumbling across a bird, and the other close behind pointing a shotgun mic (not a shot gun!).

I also found myself making other ecological observations. One evening I set my equipment up on a tussock dominated slope. Some ten minutes after commencing my recording the repeating warning call of a willow warbler came into earshot, a sound seemingly incongruent with the surroundings. I then realised that down below, out of view, was a gully that had been fenced off and planted with native trees and left to ‘rewild’. It struck me how even small areas of unmanaged habitat can attract in a new species. (I revisited the gully one morning this summer and heard the willow warbler again, as well as tits, robin, a deer and the overhead cries of two buzzards being mobbed by crows.)

On the managed grouse moor I noticed how brown and lifeless the heather looked compared with the heather of more natural scrubland. Less purple blossom, less insect life. I wondered whether the heather management regime on the grouse moor meant the root structures of these plants were comparatively weaker, leaving them more vulnerable when conditions of prolonged dryness and heat prevailed, such as those we experienced in summer 2018. Or perhaps the concentrated blanket of one species meant there was just not enough water to go around? Of all the wild flowering plants I came across bramble bushes seemed to attract the biggest variety of insect species including various flies, bees, aphids and ladybird larvae.

Back at home in my attic, with a large quantity of audio and visual material of varying quality now collected, I started to think about and become a little daunted by the next stage in the process – composition! It soon became apparent that my original idea of a linear piece moving from silence to a gloriously rich ecological cacophony was not going to work. For a start, the managed landscapes and human structures had all offered interesting and sometimes loud sounds. Secondly, adding more and more wildlife sounds into the piece as it progressed produced unsatisfactory results which didn’t sound like any ecological space I had ever encountered. I thus abandoned my original plan and instead set about building a piece which reflected and respected the individual sonic qualities of the different spaces I had visited. This was altogether more satisfactory, in part because it allowed me to bring some of the essence of my experiences in the field into the piece. What resulted is sectional piece, roughly of two halves, with the first representing the more managed moorland habitats and the second the mosaic of habitats that might result if nature was left to take its course. The diagram below represents how I grouped my audio and visual material into different ‘pools’ representing different spaces, and how these were then drawn on to form the sections of the piece.

Diagram showing construction stages and sections of Rewilding

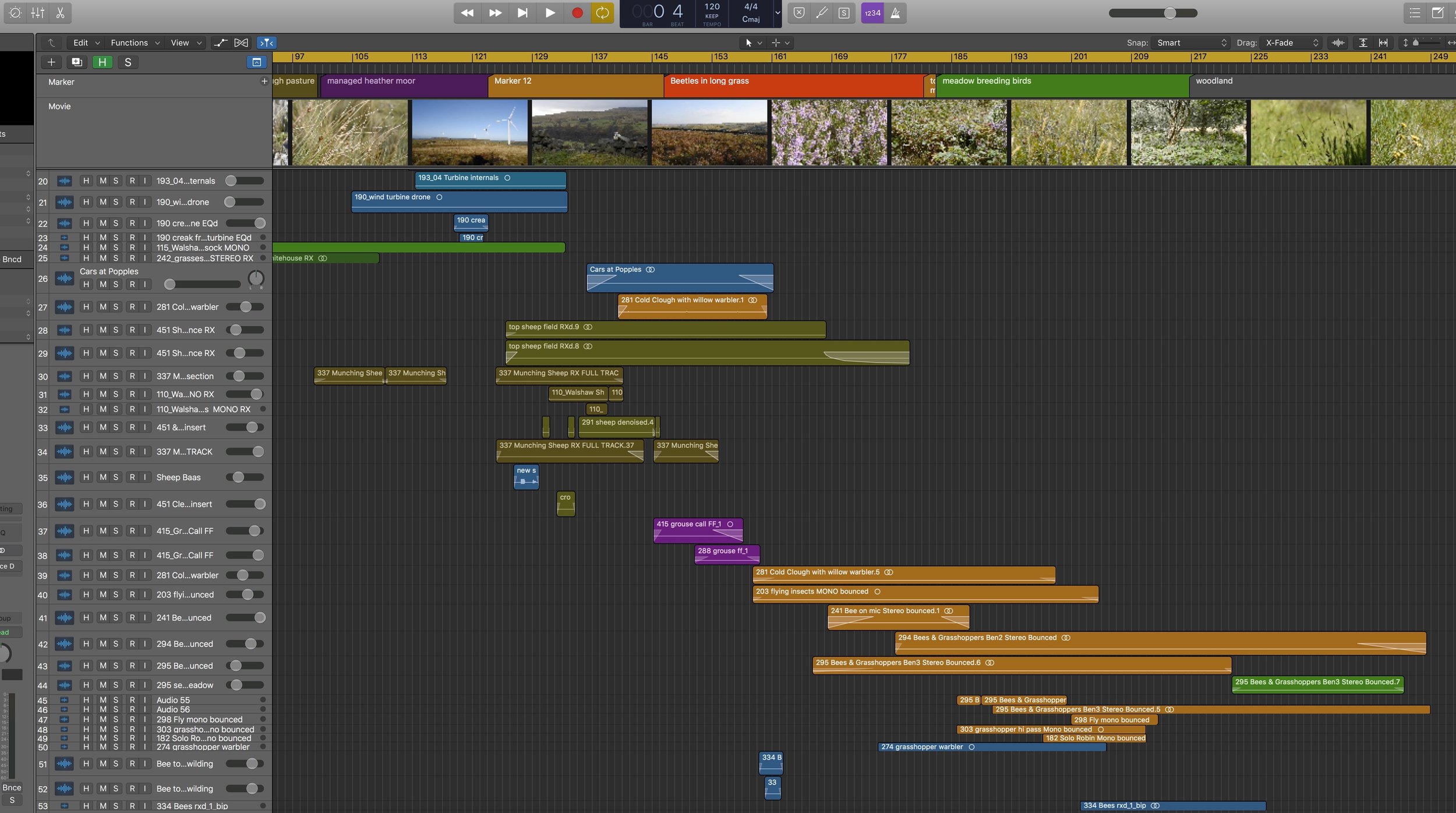

During the construction process I found the use of background ambience vital to provide audio ‘glue’ and to also help mask unwanted sounds. These ambiences provided my foundation layers, on top of which I added other sounds, sometimes purposefully fore-grounding them dramatically as a way of bringing sonic interest to the piece (e.g. flapping bird wings and deer barks). I also introduced exaggerated and hyper-real elements. Such examples include a munching insect (made from a contact mic recording of an ant hill), and crescendo-ing drones from pylons and turbines (made with recordings using electro-magnetic microphones). Having said this my over-riding aesthetic intention was to generate quite naturalistic material as I was trying to keep a connection with the believable. Overall, and in comparison to much other sound art I’ve listened to, I made relatively little use of processing or effects, relying solely on layering of sounds (although this was substantial), automation of volume, panning, corrective EQ and use of iZotope RX 6 audio repair tools. Below is a screen shot from the Logic Pro X project file. The final piece can be listened to here (scroll down this page a bit).

Screen shot from Logic Pro X project file

In making Rewilding I became deeply connected with my surroundings. I reflected though on whether others experiencing the piece would feel a connection? As a piece of ecological sound art does Rewilding help raise awareness about habitat and species loss? Will it promote any pro-environmental behaviour? Rewilding of the moors would be a complex, long-term and highly political project – it is hard to identify any small acts of activism interested individuals could take to change the current status quo if they felt inclined. There are however several local bodies engaged in restoring moorland habitat and at the end of Rewilding I provide sign-posting to these initiatives.

I have also thought of several ways in which I could further enhance the knowledge-base, or experiential side of things for people including (i) providing information on the specific locations chosen for recordings such that those wishing to could visit and experience them first hand and (ii) providing a guide for listeners, identifying the species that can be heard at different points in the piece.

Ultimately though for deeper connectedness I feel the public would need to have direct involvement in making and performing such work. My future interests lie in exploring this aspect further. As a field recordist, with some knowledge of my local environment, and some creative skills may be there is a role as a facilitator for others’ creativity, i.e. - handing the role of ‘maker’ to others so they can connect more intimately with nature and gain the most immersive experience possible. Such creative activities might include soundwalks, field-recording workshops and compositional activities.

References

Gilmurray, J. (2018). Ecology and Environmentalism in Contemporary Sound Art. (Doctoral thesis). Retrieved from http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/13705/